Fighting for Justice

SHAHBAZ Bhatti walked out of his mother’s home, stepped into a waiting car and drove away. Moments later, his mother heard the deadly thunder of an assassin’s bullets banging into the vehicle and killing her son.

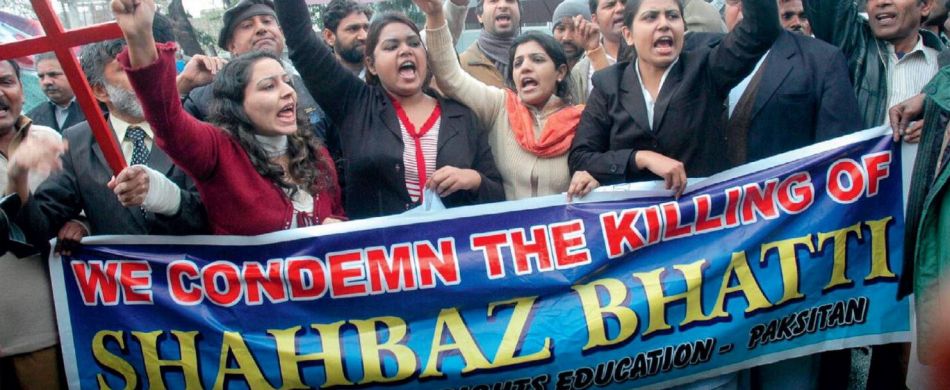

The murder by the Taliban in this quiet Islamabad suburb on 2 March 2011 seemed to have the immediate effect of vanquishing any hope among Pakistan’s suffering Christian minority of some two million people that they might one day enjoy the justice, freedom and equality promised to them by Mohammad Ali Jinnah, their country’s founder, in 1947. Furthermore, the prospect that the hated blasphemy laws used to persecute them might be either reformed or repealed now looked more remote than ever.

For a moment, on that miserable day of despair, it appeared that the murder of Mr Bhatti, the Federal Minister for Minority Affairs, had also killed off a dream he had actively nurtured for some 28 years of his short life.

Close brothers

Mr Bhatti was 42 years old at the time of his assassination. One of six children of a Catholic family, he was particularly close to an elder brother, Paul, but the pair had seldom seen eye to eye on the approach to the intolerance convulsing their country.

Whereas the experience of religious persecution and injustice galvanised and fortified the will of Shahbaz to confront and change the situation, Paul’s initial reaction was to retreat, to try to escape from the enormity of a problem he felt he had no power to change.

A surgeon who had trained in Padua, Italy, Paul returned to Pakistan to serve the poor of his country as a missionary doctor rather than a politician. He swiftly took his family back to Europe when he awoke one morning to find extremists attempting to cut through steel bars on the windows of his residence.

Paul’s departure was one of the most disappointing moments for Shahbaz. The pair would argue frequently afterwards. Shahbaz continued to try to persuade Paul to return to Pakistan, while Paul urged him to leave for the safety of Europe. “You are calling me to leave paradise for hell,” snapped Paul one day in response to yet another entreaty from his brother, only for Shahbaz to answer, “The road to paradise starts in Pakistan.”

It was only after the assassination of Shahbaz that Paul realised he had been “arguing from a rational and human perspective with a man whose gaze was fixed on heaven.”

When Shahbaz was gunned down he returned immediately to Pakistan with the firm intention of relocating his entire family to Italy and Canada, angrily deeming his home country unworthy of the services of his family, but his experiences in the following few days changed his mind – and his life – forever.

A defining moment

“There was a sea of people in attendance at his funeral,” recalled Dr. Bhatti, “women, men and children, from all walks of life, politicians, diplomats, Christian, Muslim, and Hindu religious leaders – all desperately crying for Shahbaz, all crying, ‘Who will take his call for love?’

“When I accompanied his body by helicopter to our native village of Khushpur, a throng of young and old people overwhelmed me, crying and sobbing; distraught they had lost their champion for freedom. It was impossible to console them. They were broken-hearted, struck with grief in the loss of Shahbaz. He was like a father to them and they were now orphaned.

“I was astounded by the lasting power of his sacrificial love, now living in the hearts of the people,” he said. “I know that in reality, it was the love of God. And in the midst of this vast demonstration, many Muslim leaders were chanting, ‘Shahbaz your mission will continue! Shabbaz your mission will continue!’ And then many of these people turned and looked at me, saying, ‘Now what?’ This was an extraordinary and defining moment for me.”

Forgiveness and love

Indeed, there would be no going back for Dr. Bhatti, but as he reflected on a new sense of vocation he felt impelled to discuss his future with his grieving mother, approaching her hesitantly and with timidity in the knowledge that the task of retrieving and carrying the fallen standard of religious freedom in Pakistan could come at a terrible price that might inflict further suffering upon her.

He was amazed by her reaction. “My mother told me, without hesitating, that Shahbaz’s mission should continue, and I was the right person for the job,” he said. “She then told me that it was Shahbaz’s will that I return to Pakistan and that now it was God’s will.”

Soon afterwards, Dr. Bhatti was appointed by the government to the position held previously by his brother, and also assumed chairmanship of Shahbaz’s political party, the All Pakistan Minorities Alliance.

Learning again from his deeply Catholic mother, he started his new mission with a heart of forgiveness and love, virtues he describes as the “ultimate weapons of revenge.”

Mohammad Ali Jinnah

The intentions of the Bhatti brothers was to restore a Pakistan disfigured by extremism to the original vision of Mohammad Ali Jinnah, a man who, on 11 August 1947, promised in his first presidential address that minorities would have the same equal rights, privileges and obligations as the majority. “You are free; you are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques or to any other place of worship in this State of Pakistan,” Jinnah had told the people of his country. “You may belong to any religion or caste or creed that has nothing to do with the business of the State.”

Instead, the Bhattis had grown up in a world of political assassinations, religious persecution and sectarian violence, wars and internal and cross-border terrorism spanning decades. They have witnessed Christians subjugated, oppressed, enslaved and sometimes murdered, often with the connivance and complicity of the police and the authorities, and especially under the blasphemy laws.

Shahbaz responded to this grotesque aberration of the country he loved partly by fighting for quotas for the representation of religious minorities in government, establishing committees for inter-religious dialogue, by promoting and fostering good relations between Muslims and other religious traditions and, of course, by campaigning against the blasphemy laws, the act which cost him his life.

Led by the Holy Spirit

Dr. Bhatti has steadily built on his brother’s achievements by, for instance, advocating an education curriculum that addresses causes of hatred, discrimination and division. He has sought to empower women and the marginalised, and has fought for electoral reform in the hope that religious minorities might be represented at every level of politics. He has also championed innocent victims of hate crimes, including those falsely accused of blasphemy. The fight indeed goes on, inspired by the memory of his brother, whom he now describes as “an agent of change led by the Holy Spirit.”

Ray of hope

At a meeting in the Houses of Parliament in London in November, Dr. Bhatti spoke of his hope that Pakistan is finally beginning to improve as a result of the heroic efforts of those who have gone before him.

He acknowledged that “we are still facing the cruel and harsh realities of violence against the weak and voiceless people of our community,” before adding, “I am pleased to share with you that I feel and see that Pakistan is changing. Present military and civilian operations against terrorism are bringing fruits,” he explained. “All extremist organisations are banned, most terrorist groups are weakened, my brother’s killers have been arrested, and one was killed. The people of Pakistan are gradually coming out of oppression and fear, which has dominated them for many years.

“The Supreme Court recently upheld the death sentence of a police bodyguard who killed Salmaan Tazeer over his support for blasphemy law reform, and other verdicts have given us great hope for the future of Jinnah’s Pakistan, where everybody can live in peace, dignity and without fear, honouring each other’s faiths.

Recently Pakistani leadership participated in the celebrations of our Hindu brothers and sisters (Divali), giving a statement that there is no discrimination between majority and minority,” Paul said.

“We want this Pakistan, a country without any discrimination among people of diverse faiths, where the weak and the oppressed may feel safe and respected… this is the path we are following – indicated by Shahbaz – to see our beloved country where there’s no discrimination against religious minorities.”

Cultural genocide

At the same meeting, however, came several reminders of just how much work remained to be done. They included the testimony of a 36-year-old Catholic mother who fled to England on a false passport after she witnessed her husband battered to death by a gang who targeted him because he had a supervisory employment role which put him in a senior position to some Muslim employees.

However, after she complained to the police she was imprisoned for two days, then tortured with lit cigarettes by some of the men she had named as her husband’s killers. With the complicity of police officers, the men, she said, then raped her. She is now seeking asylum in the UK, but she is pessimistic about her prospects of being allowed to remain – and is terrified about what might happen to her and her 10-year-old son if they are returned to Pakistan.

Wilson Chowdhry, of the British Pakistani Christian Association, told the meeting that in his view Pakistan remained in the grip of a “cultural genocide operated by the people living next door to you.”

There can be no doubt whatsoever that Dr. Paul Bhatti, like his murdered brother Shahbaz, is heroically doing his utmost to help the victims of such horrific violence, fighting for justice while appealing to the consciences of moderate Muslims and striving to build bridges over barriers of ignorance, hatred and distrust.

He is a man of deep humanity, culture, learning and immense bravery who has united his own struggle to that of his departed brother. “I am committed to continuing this struggle even if the ultimate goal requires my sacrifice too,” he said, almost as a casual aside, as something taken for granted.

Touching reminder

One of the last things I saw Dr. Bhatti do on his visit to London was to crouch down to touch a plaque in the floor of Westminster Hall that marks the site of the trial and condemnation to death of St. Thomas More, the great man of conscience who is now revered as the patron saint of politicians.

It represented a poignant glimpse of Christians united across the ages and the continents by Our Lord’s words in John 15:13 that, “no-one can have greater love than to lay down his life for his friends,” a lesson Dr. Bhatti knows only too well.