God & I: Michael O’Brien

YOU are a cradle Catholic, but at a certain point you decided to leave the faith. Why?

As a young man during the 1960s I was deeply affected by the spirit of social revolution infecting the atmosphere and culture of the Western world. It was presented to the young of my generation as highly idealistic, as heroic, and of course very pleasurable. At the same time the light of the Gospels was denied all around us, and the Church was unceasingly mocked and slandered. I imbibed the poison, stopped going to the sacraments and ceased praying. I soon drifted out of my Catholic faith, thinking that I was leaving behind a ‘myth’ that was no longer real.

What eventually brought you back to the Church?

A great shock brought me home to my faith. As my intellectual falsehoods and moral confusions increased, I felt a void growing within me. After years of this pride and rebellion, of thinking myself an autonomous being, superior and free, God permitted me to see the actual condition of my soul. He allowed radical evil to assault me as a spiritual presence that was so dark and terrifying that I felt paralyzed, totally helpless to defend myself from it. But at that very moment, I cried out to God and he rescued me from this dark spirit. At the same moment I was given instantaneous knowledge that everything the Church and the Gospels had taught us was true – it is the ultimate Real. In the months and years that followed, the Lord helped me to find deep healing and to gradually discover the path for my life in him.

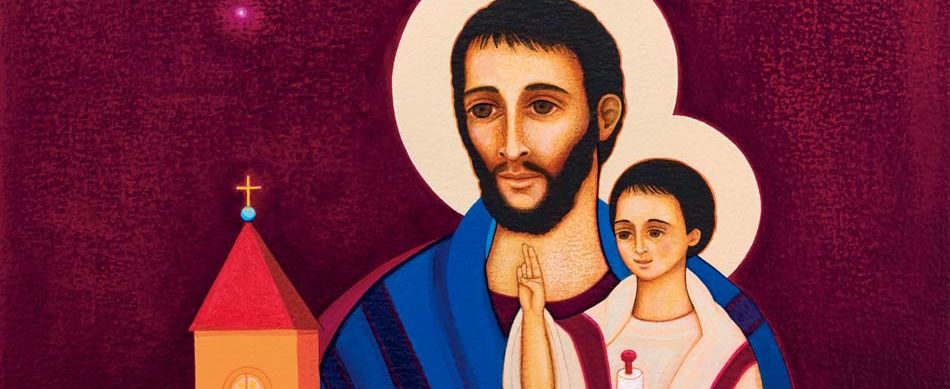

You are a writer and a painter of myriads of icons and other works of art. Most of your art works feature explicit Catholic themes. Do you feel you have a ministry of upholding Catholic values through the arts?

Yes, I see my life as a Catholic painter and writer as a vocation, or more precisely as a mission to help restore culture. Many gifted young Catholics are faced by the dilemma of trying to survive as artists during a time of history that works relentlessly to banish the voices of truth and love from the mainstream of culture. These good young people wonder if they should compromise a little, in order to survive. This is always a mistake, as it so easily leads to the loss of faith and the loss of their unique creative gifts.

I should add that there is a legitimate calling to create beautiful, wholesome works of art that are not necessarily overtly Christian. At the same time, there should be a vast outpouring of inspirations that give ‘flesh’ in beautiful forms to the truths of our Faith – in other words, overtly Christian works. But to choose the path of overtly Christian creativity is much more difficult and meets with merciless resistance in the world. Thus, a great deal of courage is needed – courage and grace. If we hope to bring streams of fresh water into the polluted culture of our times, we must pray very much for both.

You are the author of several novels, including the seven-volume Children of the Last Days series. What message do you want people to take away from your writings?

I’ve written hundreds of thousands of words, in fiction and non-fiction, but I think it all might be condensed to this: God is our father and he loves us. The fourteen novels I’ve written tell a broad spectrum of stories about human life, and in all of them I try to reveal the hidden greatness in man, without minimising his wounds and blindness. Another key theme in my work is that God does not promise any of us a safe, comfortable life, but he does promise us a life of true greatness, if we would only look up and let him take our hand in his.

What qualities must a good Catholic writer have?

The Catholic writer must be conscious of two main dimensions in his calling. The first is to be involved in the lifelong labour of perfecting his skills as a writer. The second, and most important, he must be praying constantly for the good of the work he is making and for the good of those people who will one day read it. These two principles are the same for all the arts. Divine grace and our natural human talents then work together to bring something new into the world that gives life to others.

What was the most painful moment in your life?

As I described it above, the moment of my conversion was the most painful. It was the pit of total darkness, total terror, and absolute abandonment. But I must say that it was also the most beautiful moment of my life, because there at the bottom I met Jesus Christ. I learned that we are never alone. Even in very dark situations he is with us.

In that moment did you feel that God was with you or did he seem far away?

It began with total hopelessness, and then from a small spark in my soul a weak but desperate cry leaped out of me: “O God, save me!” Instantly, the horrifying presence of evil retreated, and the peace of God filled me for the first time in many years. Then I knew that He was not far away – he is never far away – if only I would look up, if only I would ask.

Was it hard for you as a father of six children to raise them in the faith?

Yes, it has been very difficult, considering the surrounding culture, which assaults faith at every turn. In our family culture we have focused on art, literature, music, games, fun, laughter. We never had a television in our home while our children were growing up, and only in recent years the internet. Because we often lived in remote regions of Canada, my wife taught our children at home. Later, the anti-life, anti-family governments of our country, increasingly aggressive in promoting radically immoral or unhealthy social revolution agendas, further encouraged us to persist in home-schooling. We had a lively parish life and regular prayer life at home, and a circle of friends who were living much the same way as we were. This greatly helped. With six children and minimal income as a Christian artist, our way of life was hard, involving countless sacrifices, but now, all these years later, the good fruits are visible. It’s so moving for my wife and I to see our married children home-schooling our twelve grandchildren, focusing on faith and culture in their homes.

English writer Malcolm Muggeridge, who converted to the Catholicism at the age of 79 thanks to the influence of Mother Teresa, once said, “I look forward to death with colossal joy.” Does death frighten you or give you a sense of peace?

I cannot say that I have ever looked forward to my death with “colossal joy.” However, whenever the thought of my own death comes to mind, I do feel peace. Most importantly, I see it as the moment when all that my life has been, all that I am, can be offered to Him in total abandonment. Into your hands, O Lord, I commend my spirit!

How do you perceive God?

I try to perceive God as our Father, just as Jesus describes Him. I pray to him as a child speaking with a loving father. As I get older and older, I have come to understand that his apparent “silence” is, in fact, a deeper speaking of total Presence. We do not hear him speaking because we are very deaf. Only in quietness of heart and soul can we learn to listen – and then little by little we can come to know that he loves us beyond measure. In our contemporary world so full of noise and frantic pace, it is difficult for us to understand this ‘language’ of the soul, and yet God is always seeking to help us learn it if we respond to grace and seek his will totally.

What implication does your idea of God have in your life?

It has shown me that the face of love itself need not be “talking about” love, but is more about being a presence of love for others, in our acts, gestures, and attitudes, and often simply by being reliable – being there for others as a presence of love for them, attentive to them, suffering with them, rejoicing with them. And often most powerfully when we are not talking, but simply being with them. This impacts my life as a husband and father, and also in my creative work. It may sound strange for an author to say, but I think that more is accomplished between the lines of my novels than with the actual words. In my stories I strive to reveal the hand of divine providence at work, even when we cannot see it.

T.S. Eliot wrote, “The majority of mankind is lazy-minded, incurious, absorbed in vanities, and tepid in emotion, and is therefore incapable of either much doubt or faith.” Do you think this definition is still valid today?

Eliot’s somewhat melancholic portrait of humanity is generally true, and indeed more true than ever in our times. However, I would underline the fact that grace and divine providence are always at work, and that Our Lord never ceases to draw all souls to himself, that we might know ourselves as beloved sons and daughters of our Father-Creator. That we might become free of our addiction to moral relativism, our blindness, our various forms of slavery. It may be that the increasing trials and tribulations of the modern era, created by our own human sins and errors, are permitted by Him so that we may be shocked out of our indifference or lukewarmness. It is ‘tough love’, but it is love.

In an interview you said that the biggest influences on your faith and career are “the saints and gifted artists whose lives bear witness to the fullness of life in Christ”. Were you ever inspired by St. Anthony?

Need I say that my wife and I have often prayed for his help in finding lost things – and he has never let us down. But my main experience of him is when I have asked him to intercede for me in my public speaking. His phenomenal gift as a preacher and converter of souls is often eclipsed by his gift for finding lost car keys. Yet, many times I have gone up to a microphone, scheduled to give a major talk or lecture, but mentally empty. In this impoverished condition, I silently plead for the help of the Holy Spirit and the special intercession of St. Anthony to give me the right words to say. Then, a little trickle of words begins and swiftly becomes a torrent. He is powerful with God – far more than we usually think.

What are you working on at the moment?

I’m involved with my publisher Ignatius Press in the editing stage of my novel, The Sabbatical, which is scheduled for publication in late summer or early autumn 2021 – God-willing. In the meantime I’m about halfway through writing an historical speculative novel, By the Rivers of Babylon, which portrays the early life of the prophet Ezekiel before his great visions began. The story is pouring out, both the content and process endlessly surprising me. Grace and nature, of course. It’s my hope, as with all my writing, that I may hear and create rightly, according to the spirit of the sacred scriptures.

BORN IN Ottawa in 1948, Michael O’Brien is the author of thirty books, including twelve novels, which have been published in 14 languages and widely reviewed in both secular and religious media in North America and Europe.

His essays on faith and culture have appeared in international journals such as Communio, Catholic World Report, Catholic Dossier, Inside the Vatican, The Chesterton Review and others. For 7 years he was the editor of the Catholic family magazine, Nazareth Journal.

Since 1970 he has also worked as a professional artist, and has had more than 40 exhibits across North America. Since 1976 he has painted religious imagery exclusively, a field that ranges from liturgical commissions to visual reflections on the meaning of the human person. His paintings hang in churches, monasteries, universities, community collections and private collections throughout the world.

Michael lives in Barry’s Bay, Ontario, where he is Artist and Writer in Residence at Our Lady Seat of Wisdom College. He and his wife Sheila have six children and twelve grandchildren.

Among his most notable books and novels are: The Art of Michael O’Brien – Selected Paintings; Elijah in Jerusalem; Island of the World; The Father’s Tale; The Fool of New York City; The Lighthouse; Voyage to Alpha Centauri and Father Elijah – An Apocalypse, all published by Ignatius Press, and The Family and the New Totalitarianism (Wiseblood Books).