Risking Everything

MOST of us have taken a human risk. When driving, we spot a yellow traffic light, speed up, and drive through. If served an unfamiliar food, we decide to sample it at the risk of finding it unsavory. We decide to invest in a new company, hoping that the value of stock will increase. Diagnosed with a life-threatening ailment, we agree to try an experimental drug or cure.

Spiritual risks also exist. Reflect on the young man who enters the seminary, the young woman who enters religious life, and the layperson who joins a Third Order. All are taking spiritual risks. While trusting that the Holy Spirit is leading them, these individuals risk burnout or discouragement. Did those who leave their vocations misunderstand the Holy Spirit? Not necessarily. They misunderstood the Holy Spirit’s final goal.

In spiritual risk-taking, the Holy Spirit often leads souls into a religious vocation in order to mature them. Maturity enables them to recognize and move into the vocational path that God actually desires for them.

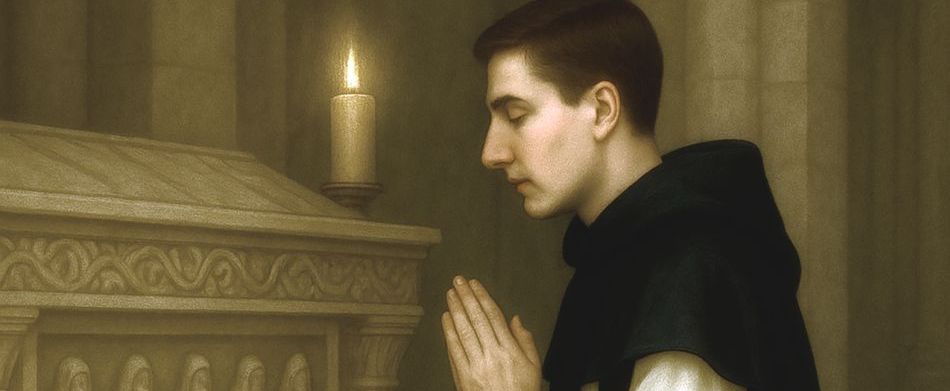

Fr. Fernando de Bulhões, the future Saint Anthony of Padua, was inspired by holy men who took a spiritual risk. He felt that God was leading him down the same path. Let’s imagine the scene.

Unanticipated request

On a pleasant June day, Brother Gonçalo was meditatively strolling through the olive grove at the brothers’ friary outside of Coimbra. Although Guardian of the friary, Gonçalo felt like one green olive among the many clustered above his head. God was all. From Him came one’s inestimable worth. So taught ‘Frei Francisco de Assis’, the reluctant Minister of their Order.

In the distance, two mounted riders caught Gonçalo’s attention. The olive grove owner coming to inspect the fruit? On previous inspections, he’d ridden a donkey. Had he saved up enough from last year’s harvest to afford two palfreys?

As the riders approached, Gonçalo could see that neither was the grove owner. The young one was dressed in a white and black habit, the old graybeard in a short brown tunic and leggings. An Augustinian monk and a servant.

At some distance away, the monk reined his palfrey and dismounted. The servant did likewise. Handing his reins to the older man, the monk strode toward Gonçalo, bowed, straightened.

“Brother, I am Father Fernando from Santa Cruz. May I request to meet with the Guardian?”

Gonçalo reddened. “I am the Guardian.”

The monk bowed again. “May I speak with you?”

“Certainly. But unlike Santa Cruz’s fine parlor, we have a reed hut. Outdoors is more beautiful than a reed hut. May we speak out here?”

“Of course.”

Gonçalo walked toward a circle of low rocks circling the ashes of last week’s fire. Later on, Brother Cook would prepare tonight’s supper if the begging friars brought back any food that needed cooking. Usually they didn’t.

“The brothers speak of your preaching, Father Fernando. Would you please offer a prayer?”

Fernando bowed his head and made the Sign of the Cross. “Come, O Lord Jesus,” his steady voice pleaded, “and lay your hand upon the soul, and she shall live by the life of grace in the present,” he paused, “and by the life of glory in the future. Amen” (Sermons for Sundays and Festivals III, p. 185 – Edizioni Messaggero Padova).

What had Gonçalo expected? An Our Father? He waited silently, knowing that his guest was mustering courage to speak.

“Brother, I am asking if you would accept me into your Order.”

Nothing could have been more startling.

“Father, look at me.” Gonçalo hoped the priest would notice the patches on his worn, grey woolen tunic. “When I wash this, my only tunic, I am in my breeches. I imagine that a laundress washes your pristine habit and you are never only in your breeches.”

Lady Poverty

Gonçalo smiled. “Follow me.” This priest from a wealthy monastery needed to see how the Poor Brothers lived.

Gonçalo pointed out the crude huts with straw beds upon the earthen floor.

They passed a vegetable garden where cucumbers were approaching harvest. “You eat fine meals,” he explained. “We eat what we beg. Or what we glean from the woods or grow in the gardens.”

They knelt in the simple stone chapel and prayed. As they left, Gonçalo explained, “We have no library. We have only the Bible, one prayer book, and a Mass book. Most of us cannot read.”

As they had returned to the fire circle, Gonçalo pointed toward the nibbling palfreys. “We are forbidden by our Rule to own or ride horses. Or to handle money. We have no servants. We are all servants to one another. Life at Santa Cruz is vastly different from here.”

Father Fernando sat on a rock around the fire mound. “It is precisely because it is vastly different that I have come. I need to give myself totally to God.”

“Have you prayed about this?”

“Every day. Many times. Especially since the bones of your martyred brothers came to rest at Santa Cruz.”

Gonçalo remembered. When the five brothers had been martyred in Morocco and their remains returned to Portugal, disagreement arose over where to enshrine the relics. Some opted for the Cathedral as the most prestigious place, while others insisted on Olivares, their friary. The queen made the decision by not making any decision. “Drop the tether on the donkey carrying the urns. Let him decide where to go. Let us see where God takes him.” The donkey had plodded to Santa Cruz, the monastery no one had considered, wandered in, and stopped in front of the altar.

“You have seen the remains of our brothers?”

“Every day I pray before them. The Lord has made it clear: I must do as they did. I must give myself totally to Him. Brother, will you receive me into your Order and then send me to Morocco?”

This is why he had prayed for ‘the life of grace in the present’ and ‘the life of glory in the future.’

“You think if you go there, you, too, will be martyred.”

“It is likely, Brother.”

“Have you discussed this with your Prior?”

“Not yet.”

“In our Order, we speak to anyone who wishes to leave to ascertain any difficulties, but if these cannot be resolved, he is permitted to leave with our blessing and prayers.”

Fernando nodded.

“But I heard that this is not so in your Order. At Santa Cruz, anyone who wishes to leave must obtain the permission of all the monks to do so. Is that true?”

“It is true, Brother.”

“We have only a few brothers here, but Santa Cruz has a huge number, doesn’t it?”

Fernando nodded.

“How will you obtain everyone’s permission to leave?”

“I won’t.”

“Then you can’t leave.”

“I will ask the Holy Spirit to obtain the permission. If God wills it, He will make it happen.”

It would be humanly impossible for all the monks to grant permission for their most popular preacher to leave. But if God wills it? Gonçalo breathed a quick prayer.

“If God wills it,” Gonçalo conceded, “I will accept you.”

Meditation

Have you ever taken a spiritual risk? What was it? How old were you? What prompted you to “step out in faith”? What was the outcome? Do you know anyone contemplating a spiritual risk? What advice might you offer? What holy people can you name from the Bible who took spiritual risks? What saints? Why might God use spiritual risk taking to achieve His plan?