Robert Lentz, OFM.

CAN YOU tell us something about your religious upbringing at home?

My grandparents came from Eastern Europe when they were children. As young adults they faced a lot of prejudice in the United States because they couldn’t speak English very well and because they weren’t ‘ordinary’ Christians. They tried to fit in better by never speaking Russian at home or anywhere else. Some of my earliest memories are stories about the Ku Klux Klan burning crosses in our neighborhoods.

As a child I grew up going to Catholic churches, but the spirituality I experienced at home was Eastern Orthodox. You could say that I was caught between two worlds, but the Orthodox world is what really formed my heart and soul.

When and why did you decide to enter the religious life, and in particular to become a Franciscan friar?

I honestly can’t remember ever wanting to be anything but a religious. In second grade I wrote a little essay about what I wanted to be when I grew up. My mother saved it and showed it to me many years later. I said I wanted to be a Franciscan friar, like the missionaries I had heard about in grade school – the Spanish Franciscans who worked in the southwestern part of the United States where we were living. As I grew older I had to argue a lot with my father about becoming a religious, because he wanted grandchildren.

Where did you get the initial interest in the ancient icon tradition?

I loved the icons my Russian grandmother had. There was no place I could get even paper prints of icons where we lived, so I decided to try making copies of icons I found in library books. They weren’t very good. Later, when I could go to a Greek monastery in Massachusetts to study iconography, I learned the right way to paint.

Why do icon artists prefer to be called iconographers and to say that they write icons instead of painting them?

Iconographer means writer of icons. We say write instead of paint, because an icon is not just a pretty picture. It is like a book of theology that teaches you about God and the saints.

I have heard that many ‘iconographers’ pray or meditate while working on their icons. Do you do this yourself?

An iconographer has to pray. He has to be still and try to keep his mind in his heart when he is working. Without grace from God, you cannot paint a true icon. God is generous and is anxious to give us his grace, but we have to do our part. We do that by being still in prayer so that we can receive God’s grace.

What makes an icon different from any other religious painting?

As I said before, an icon is like a book of theology, it isn’t a pretty picture. It tries to show Jesus and the saints as they really are – full of grace. Grace is God’s presence in us, and we depict grace as brilliant light shining from inside the holy person. Sometimes we also distort things like perspective or anatomy, to suggest that we are showing the holy person from the point of view of heaven, not earth. Catholic religious paintings have tried to be very realistic, in a secular way, since the time of the Renaissance. In our day there is a new interest in icons among Catholics who feel the need to experience God’s transcendence in religious art.

While working on an icon, have you ever felt the presence of the person or ‘being’ depicted?

Working on an icon is hard work. Much of the time it can even seem boring. Every step, even the most humble, has to be done with care. The whole time, however, you are supposed to be still and pray. Because you are praying, you are in God’s presence and in the presence of God’s saints, including the saint you are depicting in your icon. That is bound to have an effect on you. I always end up knowing the saints in my icons in a personal way. At the same time, you have to be careful that you really are responding to grace and not going off on some flight of fancy. Like everything in our spiritual life, iconography can make you crazy if you are not humble.

On the cover of this June issue of the Messenger we feature your famous icon of St Anthony of Padua. Can you give our readers some explanation about it?

We get so used to familiar images that we sometimes don’t even pay attention to them any more. In my icons I try to find new, fresh ways to show the saints. I guess it is an attempt to wake people up so that they can see again. We all know that St. Anthony was a famous preacher who worked among crowds of people. What we sometimes forget is that he was also a great contemplative who needed time alone so that he could give his heart over to prayer. At the end of his life a nobleman in Camposampiero built him a little hermitage up in a walnut tree out in the woods. I put him on a branch of that tree, outside the hut, so that I could show him better. I also made him chubby, because that was what he looked like in the last months of his life when he was suffering from dropsy.

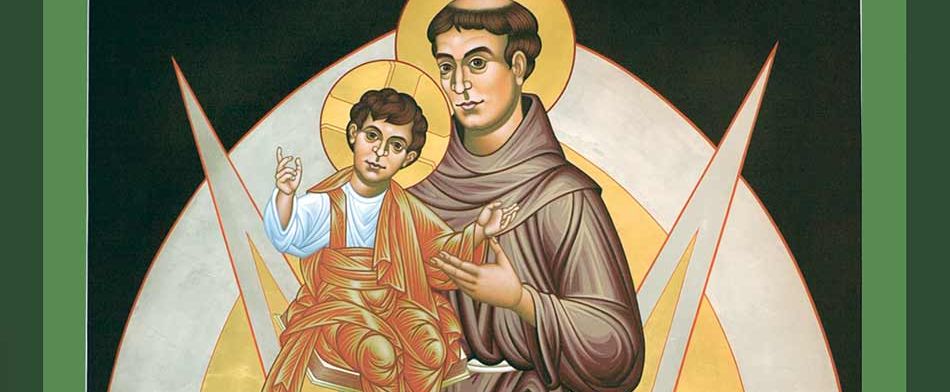

You have also painted another icon of St Anthony, one which shows him embracing the Child Jesus. This icon now stands in the motherhouse of the Franciscan Minors in Manhattan, New York. What can you tell us about that icon?

When iconographers depict Jesus at his transfiguration in divine glory on top of Mount Tabor, they surround him with concentric spheres of golden light. The light is spherical to emphasize that it is eternal and divine, just as circles have no beginning or end. The night the Christ Child appeared to St Anthony outside Padua, the nobleman who witnessed the miracle was drawn to the Saint’s hermitage because he noticed a brilliant light shining from it. When he peeked through the doorway, he saw that the light was shining from both Jesus and the Saint. This was the same light that shone from Jesus at his Transfiguration, the light of grace that shines from every saint in icons. In this icon I borrowed the symbol of the concentric spheres of light from icons of the Transfiguration to emphasize this.

Most images of St Anthony with the Child Jesus focus on tender sentiment. They make him approachable, but reveal very little of his true greatness. As a Byzantine iconographer, I wanted to emphasize the intimate union St Anthony had with Jesus during his life. While he may be famous for his preaching and miracles, he was first of all a great contemplative who spent as much time alone with God in silent prayer as he could. Union with Jesus is the most important miracle that can happen in any of our lives. Though we may turn to St Anthony with all sorts of requests, our main prayer should be that he would help us open ourselves to the brilliant light of God’s grace. To emphasize how important this is, instead of depicting the Christ Child hugging the saint, I have him facing us, with his arms outstretched, inviting us to the same intimacy he shared with St Anthony.

St Anthony died almost 800 years ago, yet millions of people continue to come to his shrine here in Padua. Why is this Saint so appealing to people today?

I believe people love St Anthony because they know he cares about their very ordinary lives and their many problems. He is like St Nicholas of Myra. We love the saints who love us.

Has St Anthony ever played any particular role in your life?

I am attracted to St Anthony because he shows us how we can combine different parts of our lives as friars that sometimes seem contradictory. He worked among the people, but he was also a hermit. He was a famous scholar and professor of theology, but he was not too proud to get his hands dirty with humble, physical work.

Which of your icons are you particularly fond of, and why?

As a Franciscan I have written many new icons for people who are struggling for peace and justice at the edges of society. Some of my icons have been written for Christians who live in Africa, Asia, or other parts of the world where traditional imagery from Europe is foreign. These icons have made me famous, and many people might think they are my favorites. Instead, the icons I especially love to write are the old-fashioned ones from Russia or Greece. Like St Anthony, while I may spend much of my energy as an artist in the busy byways of our modern world, I have a hidden contemplative side that is most at home with our ancient tradition.

How would you define God?

Your question puzzles me. As a Byzantine Christian, I can only think of God as a person. You cannot define a person with words. The only way to know a person is by living with them. We live with God when we are people of contemplative prayer, like St Anthony. What we know this way can’t be put into words. The best we can do is describe the person we have come to know, but that isn’t a definition.

People who are in love desire to have an intense relationship with the beloved. How do you cultivate a deeper relationship with God?

The only way to cultivate a deeper relationship with God is to grow in humility. As long as we think of ourselves as the center of the world, there is no room for God in our lives. Actually, if that’s the way we are, there isn’t even room for other people in our lives. The path of humility is endless. It’s the path of repentance. The more humble we become, the better we know God and the more we love him.

Have you ever thought of painting God in an icon?

Again, as a Byzantine Christian, I remember Jesus’ words that no one has ever seen the Father except the Son, and that anyone who sees him sees the Father. I once had to depict God the Father as an old man in a large icon in an altar screen to satisfy a parish priest. I felt uncomfortable as I worked on the icon. People liked it when it was done, but I felt I had betrayed Sacred Scriptures. The only way I will ever depict God in the future is in an icon of Jesus. Jesus is the only face of God we will ever know. In fact, it is only because of Jesus’ Incarnation that we can make icons of God.

BORN in rural Colorado in 1946 to a family of Russian descent and of Russian Orthodox background, Robert Lentz originally intended to enter the Franciscan Order as a young man in the 1960s, joining the formation program for St. John the Baptist Province, but left before taking his vows. Afterward he was inspired by his family’s Eastern Christian heritage and became interested in icon painting. He took up formal study in 1977 as an apprentice painter to a master of Greek icon painting from the school of Photios Kontoglou at Holy Transfiguration Monastery in Brookline, Massachusetts.

During his time in the Secular Franciscan community in New Mexico, Lentz developed a close relationship to the local friars, and again felt the call to join the order. He was received into the Order of Friars Minor in New Mexico in 2003, and transferred to the Holy Name Province on the East Coast in 2008. After relocating he taught at St. Bonaventure University. He is currently stationed at Holy Name College in Silver Spring, Maryland.