God & I: Michael Symmons Roberts

JEANETTE Winterson once called you “a religious poet for a secular age.” What does that mean to you, and can poetry still speak to people about God today?

It means a lot. I’ve long admired how Jeanette engages with belief and doubt. And I’m not even sure we live in a truly secular age; it feels more like an age of uncertainty – people still search for meaning and the divine, even without traditional religious language.

As for poetry, I don’t see it as a way to talk about God. If you begin with a message the poem usually dies. Writing is how I discover what I believe – an ongoing conversation between faith and doubt. When people read my poems, they’re simply overhearing that inner dialogue.

As a teenager, you were a convinced atheist, yet your studies at Oxford gradually opened you to faith. Was there a particular moment or experience that changed your heart?

I wouldn’t say there was a single dramatic moment, but rather two key stages. The first was the slow unravelling of my atheism. Ironically, the philosophy I was studying – meant to sharpen my skepticism – ended up dismantling it. I’d assumed that if you stripped away religious illusions, you’d reach a solid foundation of pure, atheistic reason. But I came to see that no form of knowledge rests on pure reason alone: every worldview has its own faith commitments, and once I grasped that, atheism no longer convinced me.

After that, I drifted for a while – reading widely, exploring different spiritual traditions, trying to make sense of what I’d lost and what I might find. The real turning point came when I realized I’d been asking the wrong questions. I was trying to think my way to belief, as though faith were a philosophical equation to solve. But truth, I came to see, isn’t abstract – it’s relational. It’s not an idea, but a person. That recognition – the sense that truth could be encountered rather than merely understood – finally opened the door to faith.

How did your conversion to Catholicism shape not only your beliefs, but also your way of seeing the world?

It was a gradual journey. I explored many traditions but was ultimately drawn to the Mass – the mystery of the Eucharist. I remember, when I was a documentary filmmaker at the BBC, filming a Mass when I wasn’t even sure I believed, yet feeling a deep longing for the Host as I filmed people going up to receive it. That moment stayed with me.

Writers and artists like Simone Weil, Olivier Messiaen, Dante, and David Jones also guided me. Through them, I came to see Catholicism not just as belief, but as a way of seeing – a vision of the world as sacramental, layered, and alive with grace.

You were born and raised in Lancashire before moving south with your family. What memories of your childhood still shape your imagination and your sense of faith?

Ours wasn’t a particularly religious home – more gently secular. We went to church at Christmas, but faith wasn’t really discussed. Still, it was a warm, close family, and my parents encouraged my sister and me to read and think. That openness gave me a lasting curiosity and a desire to seek truth.

I moved back north about thirty years ago, when my wife was expecting our first child, and we’ve felt rooted here ever since. Teaching at Manchester Metropolitan University, I feel a strong bond with the landscape and the spirit of the North – it continues to shape both my imagination and my faith.

Your journey took you from journalism and broadcasting into poetry and teaching. Looking back, do you see God’s hand guiding those turns in your life?

Yes, though at the time I wouldn’t have called it guidance. In hindsight, I can see a kind of vocational pull toward poetry, even when other interests – music, sport, or art – tempted me away.

I was always drawn back. It felt less like a choice and more like a calling. I remember trying to write a poem about a tree at age 6 and thinking, This is what I’m meant to do. That sense has never really left me. Of course, a sense of This is what I’m meant to do doesn’t mean you will be any good at doing it! That’s why you spend your life trying to do it justice.

As a husband, father, and now grandfather, how do you live your faith within family life and daily routine?

Faith is part of who I am, and therefore part of our family life. In a noisy, distracted world, I try to live fully in the present – to be attentive and alive and connected – a discipline I see in the mystics and monastic practice.

I bring that spirit to everyday life: to Mass, to community, and to ordinary moments with my children and now my grandchild. God’s presence isn’t constant, but in these glimpses, I feel immense gratitude.

When you’re not writing or teaching, what helps you rest, pray, or stay grounded?

For rest, I do all the usual things – I love sport and music and films, and I like going to Manchester United matches with my sons, but I’m most at peace when writing.

What keeps me grounded? Christianity, especially Catholicism, is about inhabiting the physical world, not escaping it. From the Eucharist to ordinary acts of living, grace happens in the embodied world. Like David Jones, I want my poetry to be “incarnational,” fully alive in creation and grounded in the embodied world.

Some of your poems, especially in Drysalter, read almost like modern psalms. Do you see your writing as a kind of prayer or spiritual reflection?

Yes, absolutely. Writing is where most of my prayer and reflection happen. My friend and collaborator, the composer Sir James MacMillan, once told me, “When I’m composing, that’s my way of praying.” I feel the same about writing.

Of course, I pray in other ways too, but the deepest and most intense moments of spiritual reflection for me happen through the act of writing itself.

Your work often touches on suffering, healing, and resurrection. What have those themes taught you about God and about being human?

At the heart of Christianity is woundedness: it’s inevitable and central. From that comes healing, connection, and compassion.

The resurrection embodies a fierce hope. It shows that vulnerability and embodiment aren’t to be escaped but embraced. To be wounded is to risk being fully alive, and resurrection comes only through that passage. It’s not an easy path, but it’s profoundly human. The Christian story continues to teach me what it means to live, to suffer, and to hope.

How do you experience God’s presence in your life?

That’s really what all my poems are about. It’s hard to talk about God directly – that’s why we write poems, paint icons, compose music. Words struggle to capture it.

So while I could say that God is love, joy, creator, sustainer – those are really things I’m continually exploring through poetry. Whatever I think I’m writing about, I always find myself coming back to that. My next collection – Dog Star – coming out this month, is once again all about that search.

We often say that we need God – but do you think God needs us?

I do. Otherwise, why create anything beyond Himself? God’s love and freedom seem to carry a kind of need – a love that goes beyond love.

I don’t mean that we sustain God; He sustains us. But His love for us resembles the devotion between people so close they can’t imagine life without one another. That’s how I think God relates to us: a love that is both giving and deeply, inevitably connected.

Which saints have influenced you the most?

I’ve always felt a deep connection to the saints of Scotland and northern England – figures like St. Columba of Iona, and Sts. Cuthbert and Aidan of Lindisfarne. But I’m also profoundly drawn to St. Francis of Assisi, especially this year as we mark 800 years since his death.

My relationship with Francis began through the composer Olivier Messiaen, whose music captivated me long before I had any faith at all. His vast opera on St. Francis – rarely performed because of its scale – opened up Francis’ radiant sense of joy and holiness for me.

Francis feels especially relevant now, at a time when we risk drifting away from the natural world and even imagining artificial intelligence as a ‘better’ form of humanity, reminding us that we belong to creation, not apart from it.

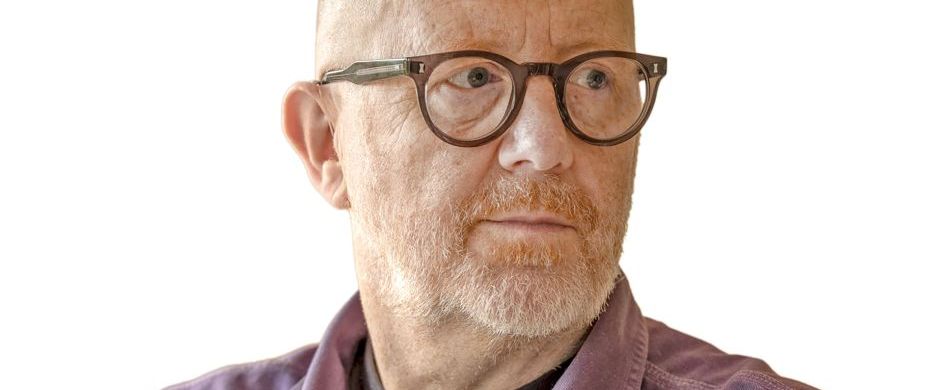

BORN in 1963 in Lancashire, Michael Symmons Roberts studied Philosophy and Theology at Oxford University. After working as a journalist and documentary maker, he became Head of Development for BBC Religion & Ethics before leaving to write full-time.

His poetry collections include Corpus (Whitbread Poetry Award, 2004), Drysalter (Forward and Costa Prizes, 2013), Ransom (2021), and the forthcoming Dog Star (2026). His collaborations with composer James MacMillan have produced operas and choral works for the Royal Opera House, Scottish Opera and Welsh National Opera; The Sacrifice won the RPS Award for Opera.

He is also the author of two novels, Patrick’s Alphabet and Breath, and the nonfiction books Edgelands, Deaths of the Poets (with Paul Farley), and Quartet for the End of Time (2025).

A Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, he is Professor of Poetry at Manchester Metropolitan University and lives near Manchester with his family. Visit his website at: symmonsroberts.com